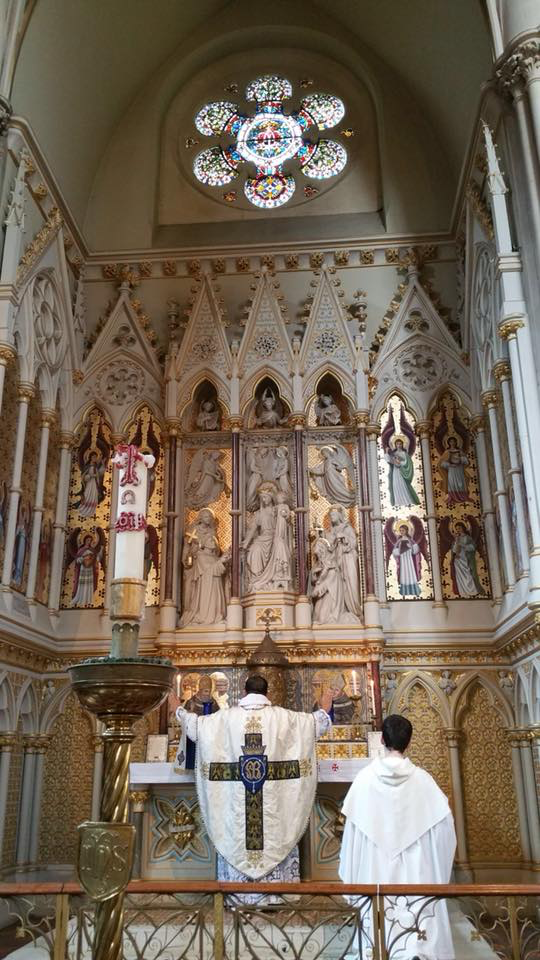

Main Image: Dominican rite 'Missa Maior' at the High Altar of the Rosary Shrine (St Dominic's Priory) in London.

Fr Lawrence Lew OP - Iota Unum Talk on the Traditional Liturgy and Catholic Masculinity, London, 31 May 2019

Themes

- Manly virtues

- Sexual distinctiveness

- Men are called to fatherhood

- Consecration to St Joseph

- The vice of mollities

- The virtue of fortitude

- Scouts of Europe

- Traditional liturgy and the virtues

Anecdotally, it seems that the traditional Mass attracts proportionately more men than modern forms of the Mass.

in the Rosary Shrine, London

This observation was made privately to me by Fr Aidan Nichols OP in a conversation we had when I was in the novitiate. And then, I mentioned this in a private conversation with a young man I met at a conference in Cambridge. I didn’t realise he was an intern from The Tablet and the next week, I found this private statement published and in print! So, depending on whether or not you trust The Tablet this may or may not be true!

Realistically, though, this is an observation we can all make for ourselves: the traditional Mass appears to attract more men and young families than your average novus ordo Mass. My experience as a university chaplain for four years up in Edinburgh has been that Catholic men who are intent on the faith and on the life of virtue – converts (and ‘reverts’) particularly – are drawn to the traditional Mass almost as soon as they encounter it; armed with a Missal or some informed reading, they quickly grow to love it.

Speaking as a convert myself, that was my experience too. However, stating the obvious like this is easy. It’s rather more difficult to analyse the phenomenon and try to answer why this is the case. Why is it that Catholic lay men in particular are drawn to the traditional Mass? What is there about its form – obviously, its essence is the same as the novus ordo’s – that appeals to serious Catholic men of our time?

Gender Revolution and Pope Francis’ response

To attempt an answer, I think we need first to speak about men specifically, and about what is proper to their nature, and about the virtues and vices that pertain to the masculine nature.

Incidentally, one of the best youth movements that I know of, and that exists to form young Catholic boys in manly virtues, and to raise them up to become good Catholic men is the Scouts of Europe. I have been privileged to work with the Scouts of Europe for a number of years now, and each time I try to start a new troop in a parish, or give a presentation about them, I am faced with protests from Catholic parents, teachers, and even priests against the fact that we do not mix boys and girls in our units, and I have to explain that boys and girls are different and they have different needs and different temperaments and characters and so they need to be formed separately and led to virtue in their own distinct ways.

Indeed, one of the many heresies of our age, which Cardinal Robert Sarah calls a “Luciferian refusal to receive a sexual nature from God”, purports that men and women are alike, gender-neutral at birth, and so they do not have specific inherent differences. Any honest parent would tell them otherwise! All this is supposedly advanced in favour of a fundamental human dignity.

In 2017, Pope Francis acknowledged this current on-going “cultural revolution” and he called on the Church to confront it. He said quite plainly: “The recent proposal to advance the dignity of a person by radically eliminating sexual difference and, as a result, our understanding of man and woman, is not right.” He added: “the utopia of the “neuter” eliminates both human dignity in sexual distinctiveness and the personal nature of the generation of new life.” And the Pope decried “the biological and psychological manipulation of sexual difference, which biomedical technology can now make appear as a simple matter of personal choice – which it is not!”

Masculinity and the Crisis of our Times

So, what makes men different from women? What constitutes masculinity? What are manly virtues?

In the first place, men are called to fatherhood, and thus to exemplify on earth and through various vocations – as priests, husbands, fathers – the one Fatherhood of God, the God from whom “all paternity in heaven and earth is named”, as St Paul says (Eph 3:15).

The increase in single mothers who are abandoned by irresponsible men; the increase in children who thus do not know their fathers; the perpetuation of the Peter Pan syndrome among men; the clerical abuse crisis; and the refusal of priests to lead people in faith and to teach the Gospel in all it fullness: these are all some of the signs of a sinful failure to exemplify the Fatherhood of God.

For the call to fatherhood is a call to lead, care, and protect a household as paterfamilias. There is a crisis of virtuous leadership, of genuine paternity in our society, and thus, also, a crisis of genuine holy masculinity in the world and in the Church. Consequently, the family itself is in crisis today. Like the gender ideology that plagues us, the crises of fatherhood and the family is diabolical.

In 2016, Cardinal Sarah walked with some two thousand Rover Scouts of Europe to Vézelay – this is a wonderful annual pilgrimage that involves the adult male branch of the Scouts of Europe.

In his address, he said to these Catholic men: “Don’t let yourselves be influenced by a Europe which is drunk on its numerous ideologies which do a lot of harm to the whole of mankind. Think of Marxism and its gulags, of Nazism and its horrors, and now the gender theory directly attacking the laws of God and of nature, destroying marriage and our societies, damaging our children as young as those of primary school age. I repeat it: the gender ideology, the disproportionate and unlimited democratic freedoms, and ISIS have all the same satanic origin. You, Scouts of Europe Rovers, if you resist this Europe without God – a Europe that proudly dominates the poor and the weak, and that denies its Christian roots – you will be preventing Europe from committing suicide and from disappearing, eliminated by more virile peoples, those more believing and prouder of their identity and of their relation to God.”

The Cardinal rightly believes that a more virile people, that is, those who are more manly, more committed to their cause and more willing to suffer for its success, will eliminate Christendom if we remain weak-willed and drunk on ideology and hedonism; if the Christian men of today do not rise to the challenge of being strong Catholic men, and if we do not work now to form our boys to become men of virtue.

Earlier this month, I had the joy of travelling to the Holy Land for the first time, in the company of two inspiring Catholic men: Jim Caviezel who played Christ in ‘The Passion of the Christ’, and the Marian priest, Fr Donald Calloway. Jim Caviezel spoke to us about his work and his mission, but the enduring thought he shared with us was his discovery of redemptive suffering, his patient endurance of suffering, through undergoing the ‘Passion of the Christ’. It seems that Our Lord gave him the essential manly virtue of fortitude so that the man who played him on film might also suffer with him. I shall, therefore, return to this virtue presently.

However, Fr Calloway also gave me a manuscript of his latest book for me to review and endorse. Fr Calloway’s mission, which he explains in this book, is to have Catholics everywhere go to St Joseph and to be consecrated to St Joseph. He wants us in our time to claim the spiritual fatherhood of St Joseph, and for us men to learn from St Joseph how to be fathers and to become good men. For, just as God led the children of Israel to the patriarch Joseph during the famine, so during the moral famine of our times, God’s children are being led to Saint Joseph to be fed by him; to be led by him out of this cultural wasteland; to be taught by him and so to enjoy St Joseph’s spiritual paternity even as Our Lord Jesus Christ did.

As Pope Pius XII has said: “If Joseph was so engaged, heart and soul, in protecting and providing for that little family at Nazareth, don’t you think that now in heaven he is the same loving father and guardian of the whole Church, of all its members, as he was of its Head on earth?” I agree with Fr Calloway that now is the time to consecrate ourselves to St Joseph, and to receive his paternal love and guidance and leadership. St Joseph will teach us, in our current crisis of fatherhood and of holy masculinity, to become Christian men of virtue.

Mollities

Before I consider the chief masculine virtues, I would like to consider the chief vice that is opposed to manly virtue. St Thomas Aquinas, the Common Doctor of the Church, refers to the vice of mollities, meaning ‘softness’ or ‘yielding’.

This is sometimes, rather distractingly, I think, translated as ‘effeminacy’. However, St Thomas says: “to forsake a good on account of difficulties which he cannot endure. This is what we understand by mollities, because a thing is said to be ‘soft’ if it readily yields to the touch.” (ST IIa IIæ, 138, 1) So, softness, I think, is as at least as good a translation of mollities.

St Thomas goes on to explain the specificity of this vice. The one who suffers from it is said to “yield to the touch” and not to heavy blows or force because he yields, as it were, to caresses and pleasures of the flesh; he has a certain addiction, so to speak, to pleasure and comfort and ease, and he will not relinquish these for the sake of the good. Hence, following Aristotle, St Thomas says that the vice of softness, properly speaking, refers to those who “withdraw from good on account of sorrow caused by lack of pleasure” so one who is “accustomed to enjoy pleasures” finds it hard to “endure the lack of them.”

Among the vices of inordinate pleasure that affect many people (but especially men) today are the vices of pornography and masturbation, and both of these lead to the more general vice of softness. For the boy who discovers these vices is habituated to enjoy pleasures, and he will not endure the lack of them, and so he withdraws from the good of chastity and, if unchecked, he withdraws ultimately from the supreme good of wanting to please and obey God, the good of spiritual friendship.

Carnal sin, therefore, has a deep spiritual root that keeps us from the good and can even keep us from heaven. Reinhard Hütter observes that in fact the vice of pornography “arises from the roaming unrest of the spirit rooted in a spiritual apathy that, again, despairs of and eventually comes to resent the very transcendence in which the dignity of the human person has its roots. The lust of the eyes that feeds on Internet pornography does not inflame but rather freezes the soul and the heart in a cold indifference to the human dignity of others and of oneself.” (cf Pornography and Acedia).

The antidote to the poison of pornography, Hütter suggests (following St Thomas) is “an active and persistent discipline of prayer”. In particular he recommends the Angelic Warfare Confraternity that is promoted by the Dominican Order, and of which I am the Promoter in this Province of England! I agree with Hütter, unsurprisingly, but I also want to keep the antidote of disciplined prayer in mind when I go on to speak about the traditional Liturgy. I also wanted to highlight the problem of unchastity which leads to softness, and we shall see in due course how one can and must be formed in spiritual chastity.

Returning to the vice of softness, there is the related vice of delicacy, whereby one seeks to avoid hard work and toil because these hinder pleasure, comfort, and ease. St Thomas thus concludes: “It belongs to mollities to be unable to endure toilsome things, so too it belongs thereto to desire play or any other relaxation inordinately.” Here, I want to draw attention to the inordinate desire for play and relaxation that St Thomas says belongs to softness.

The Peter Pan syndrome to which I alluded includes these inordinate desires. It is found among men who perpetuate the university student lifestyle; shirk commitments; avoid responsibilities and accountability; play juvenile computer games and waste time online; who live life from one holiday to the next, or from one pub crawl to the next club. The solution is to focus on true manly virtues, to learn from St Joseph the Worker, and above all, through prayer, to be focused on him who is “true Man”, Jesus Christ.

The Christocentric focus of the Mass, and the seriousness of liturgical ‘play’, particularly as it is the Sacrifice of the God-Man, is vital in this regard.

Manly Virtues

The virtue to which softness is opposed is the virtue of perseverance. St Thomas defines this “as denoting long persistence in any kind of difficult good.” (cf ST IIa IIæ, 137, 1 ad 1) Perseverance is related to the cardinal virtue of fortitude because every virtue that involves the “firm endurance of something difficult” to the end is secondary to the primary virtue of fortitude (or courage) (cf ST IIa IIæ, 137, 2). As a reminder, fortitude is the virtue of patient endurance, standing firm in the face of difficulties, following the counsel of reason and not the passions, even unto death.

Christ, who suffered and died for our salvation, because of the depth of his love for us, and because of his perfect obedience to the Father, is thus, for us, a perfect model of fortitude. In his Passion and Death, Christ exemplifies manly virtues, the truest Friend giving his life for his friends; the heavenly Bridegroom offering himself in sacrifice for the sake of his spotless Bride.

Fortitude, therefore, is, to my mind, chief among the virtues of a man. In particular, fortitude enables the man to endure difficulties and pain for the sake of the good, to endure mortifications and suffering, even death, with a view to their redemptive power and for the sake of the final good who is God. Hence, St Thomas says ”There is none that does not shun pain more than he desires pleasure. For we perceive that even the most untamed beasts are deterred from the greatest pleasures by the fear of pain.” (ST IIa IIæ, 123, 11) And among the pains of the mind and dangers those are mostly feared which lead to death, and it is against them that the brave man stands firm. Therefore fortitude is a cardinal virtue.”

St Joseph is thus called a “great lover of God” because he was “afflicted by much suffering which he endured with a wonderful fortitude.” This should give us pause for thought because many of us today might pray, when afflicted by suffering, that it should be taken from us. But the Saint, the lover of God, prays, rather, to endure his sufferings with fortitude and to persevere in virtue.

St Thomas Aquinas, when describing a manly saint, chose St Andrew, whose name in Greek is derived from the word aner meaning ‘man’. St Andrew is remembered for having preached the Gospel with fortitude, and he would be martyred for his brave preaching of the Truth. St Andrew also committed his life to the Gospel right from the start: he was the first-called, and he persevered in following Christ to the end.

Hence, perseverance, commitment, and fortitude are the chief manly virtues that I think are as necessary as ever today, especially because they stand in opposition to the softness to which we are prone in the modern world with its many conveniences and comforts.

Scouts of Europe and Manly Virtues

How are we formed in these virtues? I said earlier that the Scouts of Europe are an excellent movement for the formation of boys in manly virtues. Scouting, properly understood, is about the formation of character, as Baden-Powell called the virtues. Much of modern Scouting has become soft because it has not persevered in the Christian principles that, Baden-Powell and Fr Jacques Sevin SJ (founder of ‘Scoutisme’) insisted are at the heart of Scouting, because it has abandoned the difficult task of forming boys in Christian virtue in favour of teaching them practical skills; our age tends towards technological and skills-based knowledge rather than moral and practical wisdom.

However, the Scouts of Europe champions three main virtues that characterise the Scout, namely honesty (or integrity); self-sacrifice; and purity (or chastity). These three virtues I have already alluded to in my discussion of vices and virtues related to a holy masculinity. Cardinal Sarah, in his exposition on the virtues of the Scout of Europe, said that these three Scout virtues means that the Scout of Europe, and thus the Christian man, is called to be “always true, courageous and full of dedication for your country and for the Church, up to the total gift of your life.” We are called to “be happy and proud of the purity and virginity of your heart and of your body, in the middle of a selfish society obsessed by sex.”

What applies to the Scout of Europe, I would say, applies to all of us as Catholic men. We’re called to love and embrace the Truth, not only as propositions but as a relationship with One who changes us, to whom we conform our lives so that there is an integrity and honesty about our being called ‘Christians’. We’re called to give ourselves even to the very end, with fortitude and perseverance, for the sake of this Truth who is the person of Jesus Christ. Thus we’re also called to love his Bride, the Church. And, as St Paul says, “love endures all things” (1 Cor 13:7) Thirdly, we’re called to love chastity, which isn’t just a purity of the body, but also a purity of the soul and of the mind and intellect. Chastity is thus integral to our primary love of Truth. As St Thomas says, “if the human mind delights in the spiritual union [with God] and [so] refrains from delighting in union with other things against the requirements of the order established by God, this may be called a spiritual chastity.” (ST IIa IIæ, 151, 2).

To be ready to be formed in virtue, therefore, requires that one, first of all, delights in God, and thus longs for union with him. To this end, it seems to me, the traditional Liturgy, which brings us to delight in God and long for the glory of heaven, has been proven to be a wonderful and excellent school of virtue. Unsurprisingly, many Scouts of Europe are drawn to the more traditional expressions of the Liturgy, and their hearts are easily inclined towards the traditional Mass because they intuit its seriousness, and its conduciveness to those three Scout virtues.

The Traditional Liturgy as School of Virtue

How does the traditional Liturgy lead us to masculine virtues and form us in them?

Time permits me to just gesture at an answer, but I think we can identify three essential traits or strengths in the traditional Liturgy that correspond to the three virtues above, and which lead us to delight in God and to long for union with him in heaven.

Firstly, the traditional Liturgy is chaste. Externally, there is a sense of modesty and chastity in the veiling one sees in the traditional Liturgy. Firstly, women are veiled, following the injunction of St Paul. Likewise, other precious things are veiled, particularly those who have direct contact with the Sacred, namely, the chalice and the paten. And indeed, in a good medieval church, the entire sacred action is veiled either by a Rood Screen or by curtains suspended from the baldachino. In more modern churches, the sacred action is veiled by the sacred Ministers themselves who stand facing the Altar.

Moreover, the sacred is veiled by silence, by gestures and symbols steeped in history and tradition; mysterious but necessary, by a hieratic language and song with cadences and solemnity from an ancient culture onto which we are grafted.

All this made the Church’s Liturgy something mysterious and complex – like a woman! – to be approached with reverence; with the excitement of there being more to discover; to be treated with chaste longing and love. I recall (although I regret that I cannot now find the reference) Louis Bouyer or one of the champions of the Liturgical Movement saying that, after the Liturgical reforms of Vatican II, the Bride of Christ had been stripped and exposed for all to stare at – there is a nakedness about the modern Liturgy that causes the chaste of heart to look away, or to close one’s eyes.

St Thomas says that the virtue of chastity makes man capable and ready for contemplation. So, a chaste liturgy, enveloped in silence, invites contemplation. Indeed, in our sensationalistic age, it fosters a kind of fortitude and patience. On the other hand, an unchaste age creates an unchaste liturgy, it seems to me, or risks rendering even the traditional Liturgy ‘unchaste’ so to speak.

We should be mindful of this danger when we are tempted to incessantly photograph every aspect of the sacred Liturgy, and to then publish the photos online. Likewise, we must beware of what Dietrich von Hildebrand called ‘aestheticism’, that is, an excessive love for the pleasures of liturgical beauty, music, vestments, gold accoutrements, and so on, for their own sake. For as Josef Pieper says, “an unchaste man wants above all something for himself; he is distracted by an unobjective ‘interest’; his constantly strained will-to-pleasure prevents him from confronting reality with that selfless detachment which alone makes genuine knowledge possible.”

Any Catholic lay man must therefore examine his motives and conscience: What is it about the traditional Liturgy that attracts him? Is it one’s delight in God, in the beauty of the Mass that raise his heart and soul to God? Is it a deep desire to know Christ and to be conformed to him, united to the Blessed Trinity spiritually? Or is it an inordinate love of something more superficial? Although many of us were drawn to the beauty of the traditional Mass, and the glory of our traditional Catholic culture, there should be an examination of conscience so that, detached from worldly goods and temporal distractions, we might deepen our love for God and long for his grace.

In Washington DC, a young man I know frequently drove for over 45 minutes (each way) to serve a Low Mass, often at great personal inconvenience, and he did this out of love for Christ and the Mass. This shows fortitude and perseverance and commitment. Perhaps there are more traditional Masses, and more beautiful Masses available in London, but my experience has been that it is quite difficult indeed to find men who would give up so much time and effort for a Low Mass, or who would inconvenience themselves to travel to Our Lady’s Shrine either as an act of penance or an act of devotion.

My hope and my prayer is that the discovery of the traditional Liturgy by more and more Catholics will lead to a discovery of traditional Catholic virtues, mortifications, and spiritual exercises so that they will be formed by the Liturgy, and conformed to Christ through an increase in virtue and sanctifying grace. Hence, the traditional Liturgy fosters a holy asceticism that requires self-sacrifice on our part.

There are, of course, the Ember days and the traditional fasts that one can undertake, and the traditional Liturgy has this richness that is lacking in the modern rite. However, speaking more generally, there is also the fundamental asceticism of being obedient to the rubrics, of care and moderation with one’s gestures and postures, and, finally, the austerity and discipline of unaccompanied Gregorian chant. Many people, I know, love sacred polyphony and the Baroque. However, the Church has only one song that she calls her own, and this “plainsong” she prescribes for her Liturgy.

The givenness of the Church’s Liturgy, especially in her music, requires obedience and perseverance and self-abandonment from us, helping us order our passions, to discipline our emotions, and so to learn to conform ourselves to another, and to receive the gift of another, namely the gift of Christ’s Church and her sacred Liturgy in all its fullness.

Finally, the traditional Liturgy, if it is approached in this way, will teach us integrity of life. How? By first schooling us in humility, which puts us in our place especially in relation to God. For us men, who are called to lead and to be head of the Christian household, the Liturgy schools us, first of all, to acknowledge a divinely established hierarchy, and thus we’re brought to kneel before the One who is Head. From such humility, according to the order established by God, comes the grace, then, to become paterfamilias.

Thus even our Lord, in the Holy Family of Nazareth, learnt to live under the authority of St Joseph, the paterfamilias. The crisis of fatherhood and genuine masculinity in our time, therefore, stems from the crisis of faith, in which God is not acknowledged, let alone worshipped and adored. However, in the traditional High Mass, the hierarchical nature of the Liturgy and of the sacred Ministers arrayed around the altar, rightly makes evident the household of God the Father in which all is fittingly ordered towards the divine paterfamilias – and we are taught by God, nourished by God, and established in virtue by God.

Moreover, as Catherine Pickstock has observed, one of the features of the traditional Liturgy is a salutary fear of God and a genuinely humble approach to the divine Mysteries, in which man is repeatedly conscious of his fundamental unworthiness, drawing near and yet withdrawing because he has a holy awe before God. The truth of who I am before God, and the truth of my profound metaphysical need of God are, it seems to me, vital lessons that we all need to learn if we’re to advance in virtue at all. For as St Benedict’s Rule tells us, humility is the ladder through which we are “cleansed from vices and sins” and then ascend to a “love for Christ [and a] delight in virtue”.

The Dominican rite Mass, therefore, begins with a succinct ancient prayer that rightly envelops the whole sacred action in God’s grace, and reminds me that, as every good Thomist knows, every good human action depends on God as the Cause of all the good that we are and do.

The prayer, Actiones nostras, therefore says: “Prompt our actions with your inspiration, we pray, O Lord, and continue them with your constant help, so that every one of our works may always begin from you, and through you be brought to completion.”

With this prayer, let my talk also be brought to completion!